By Shelley Leachman. Much like a family physician who has treated you for years, computer systems could — hypothetically — know a patient’s complete medical history. A more common experience, of course, is seeing a new doctor or a specialist who knows only your latest lab tests.

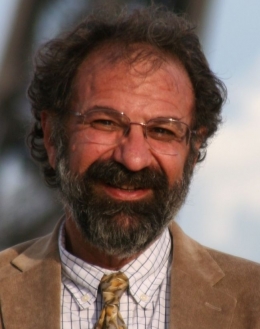

But as the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in health applications grows, health providers are looking for ways to improve patients’ experience with machine doctors. And under some circumstances, machines may have advantages as medical providers, according to UC Santa Barbara’s Joseph B. Walther, distinguished professor in communication and the Mark and Susan Bertelsen Presidential Chair in Technology and Society.

But as the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in health applications grows, health providers are looking for ways to improve patients’ experience with machine doctors. And under some circumstances, machines may have advantages as medical providers, according to UC Santa Barbara’s Joseph B. Walther, distinguished professor in communication and the Mark and Susan Bertelsen Presidential Chair in Technology and Society.

“‘Who really knows us better: a machine that can store all this information, or a human who has never met us before or hasn’t developed a relationship with us, and what do we value in a relationship with a medical expert?’” asked Walther, also director of the Center for Information Technology and Society at UCSB(link is external). “So this research asks, who knows us better — and who do we like more?”

Answer: it’s complicated.

Walther and researchers from Penn State recently collaborated on a study in which participants were randomly assigned to interact with either an AI doctor, an AI-assisted doctor, or a human physician. When patients believed they were chatting with human doctors, they preferred it when the doctor addressed them on a first-name basis. But when an artificial doctor invoked their name and medical history, they were less likely to heed AI-generated health advice.

In fact, when the machine version used the first name of the patients and referred to their medical history in conversation, study participants were not only less likely to follow that AI doctor’s orders — they were also more likely to consider an AI health chatbot intrusive. However, they expected human doctors to differentiate them from other patients and were less likely to comply when a human doctor failed to remember their information.

The findings offer further evidence that machines walk a fine line in serving as doctors, said S. Shyam Sundar, James P. Jimirro Professor of Media Effects in the Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications(link is external) and co-director of the Media Effects Research Laboratory(link is external) at Penn State.

“Machines don’t have the ability to feel and experience, so when they ask patients how they are feeling, it’s really just data to them,” said Sundar, also an affiliate of Penn State’s Institute for Computational and Data Sciences (ICDS)(link is external), in a story(link is external) by Matt Swayne of Penn State News. “It’s possibly a reason why people in the past have been resistant to medical AI.”

The team designed five chatbots for the two-phase study, recruiting a total of 295 participants for the first phase; 223 returned for the second phase. In the first part of the study, participants were randomly assigned to interact with either a human doctor, an AI doctor, or an AI-assisted doctor.

In phase two, the participants were assigned to interact again with the same doctor. However, when the doctor initiated the conversation this time, they either identified the participant by the first name and recalled information from the last interaction, or they asked again how the patient preferred to be addressed and repeated questions about their medical history.

In both phases, the chatbots were programmed to ask eight questions concerning COVID-19 symptoms and behaviors, and offer diagnosis and recommendations, explained Jin Chen, a doctoral student in mass communications at Penn State and first author of the paper.

“We chose to focus this on COVID-19 because it was a salient health issue during the study period,” said Jin Chen.

Accepting AI doctors

As medical providers look for cost-effective ways to provide better care, AI medical services may provide one alternative. However, AI doctors must provide care and advice that patients are willing to accept, according to Cheng Chen, a doctoral student at Penn State and a co-author.

“One of the reasons we conducted this study was that we read in the literature a lot of accounts of how people are reluctant to accept AI as a doctor,” said Chen. “They just don’t feel comfortable with the technology and they don’t feel that the AI recognizes their uniqueness as a patient. So, we thought that because machines can retain so much information about a person, they can provide individuation, and solve this uniqueness problem.”

The findings suggest that this strategy can backfire. “When an AI system recognizes a person’s uniqueness, it comes across as intrusive, echoing larger concerns with AI in society,” said Sundar.

In a perplexing finding, about 78% of the participants in the experimental condition claimed to feature a human doctor believed that they were interacting with an AI doctor, said the researchers. A tentative explanation for this finding, added Sundar, is that people may have become more accustomed to online health platforms during the pandemic, and therefore may have expected a richer interaction.

In the future, the researchers expect more investigations into the roles that authenticity and the ability for machines to engage in back-and-forth questions may play in developing better rapport with patients.

The researchers presented their findings at the virtual 2021 ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems(link is external) — the premier international conference for research on Human-Computer Interaction.

This article originally appeared in The Current, Wednesday, May 19, 2021, and is re-posted with permission in the UC IT Blog.