By Ann Kovalchick. There is no shortage of evidence that women in technology face particular challenges and barriers. The Center for Higher Education Chief Information Officers Studies (CHECS) conducts an annual survey of Higher Education CIO Roles and Effectiveness. The CHECHS 2017 report notes a 6% decline in the number of female CIOs, the second lowest decline in ten years. Also reported, the percentage of female CIOs expecting to retire in the next ten years reached its highest level. Given the relatively small numbers of women currently in the tech industry and the anticipated low numbers of female graduates in STEM fields, there is a very narrow pipeline of women candidates for a growing number of technology focused employment and leadership opportunities.

Less clear is what can be done to expand the role of women in tech-centric workplaces. The topic of “women in technology” presents a wicked problem, one difficult to solve due to variable and complex interdependencies. It is fundamentally a cultural phenomenon whereby both women and men learn to assign and ascribe unsubstantiated conclusions about the impact of gender on performance and ability. Nevertheless, from a practical standpoint, the problem presents itself to many women working in nearly every capacity in technical fields. Directly experiencing overt as well as covert discrimination can be dispiriting.

At UC Santa Barbara, Lisa Klock, director of Finance & Operations, is addressing the problem directly. In January of 2017 she launched a Women in Technology group as a step toward building momentum to systematically impact the ways in which women can effect change in technology fields. Lisa invited me to speak to the group on July 31 and offer strategies to counter attitudes that may threaten women’s efficacy and can be a force for change. Following are five strategies to navigate through a social environment that bifurcates individual contributions by gender:

-

Know yourself.

Developing one’s self-awareness regarding your strengths, weaknesses, motivations, needs, and sources of inspiration and renewal is critical. This knowledge anchors your actions in authenticity. By responding authentically, one is better positioned to dismiss generalizations regarding gender. There are many assessment tools such as Strength Finders, Meyers-Briggs, Hogan Personality, etc., that can help confirm (or challenge) what you believe you know about yourself. You therefore will be better prepared to understand and own the skills you bring to the table.

-

Learn to have difficult conversations.

There is abundant research noting that women who demonstrate negative emotions such as anger, disapproval, or disagreement are penalized. As a result, women may seek to avoid conflict and thus reinforce expectations that they are solely responsible for nurturing or keeping the peace. Good leadership and management demand frank and direct engagement over contested ideas. While civility is always required, cultivating the ability to explain to a subordinate why their performance is not adequate or to critique a colleague’s point of view should demonstrates that you care about the issue at hand. Learning how to do this in a respectful and constructive manner is necessary to rise above unfounded norms regarding gender roles.

-

Build coalitions.

Find like-minded partners, as well as partners with whom your perspective may diverge, though you share common goals. Build multiple coalitions across different levels of the organization that can become proving grounds for strategies and tactics. Some coalitions may be formal, others less so. Building coalitions enables you to create an accountability mesh across the organization, thereby disrupting the predictable hierarchies that serve to structurally shape perceptions of women’s value and accomplishments.

-

Embrace ambiguity.

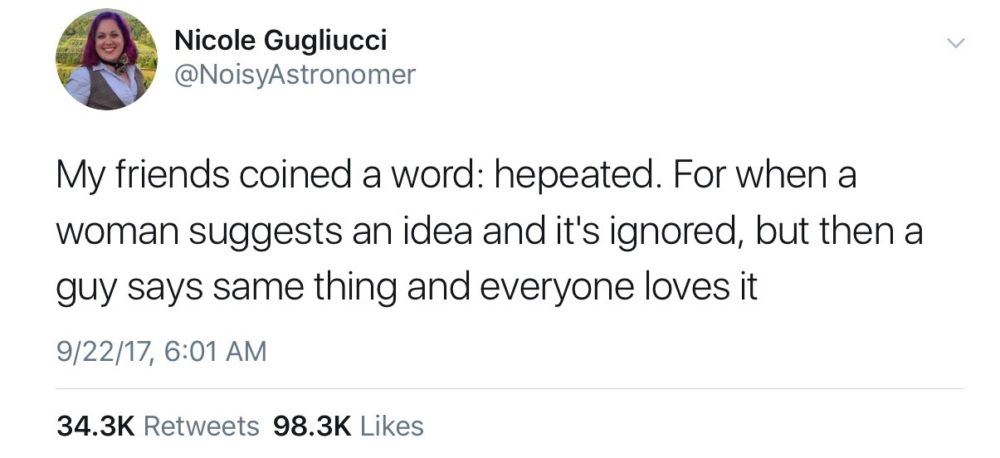

The modern work world is characterized by emergent and often chaotic change intended to be transformational. Welcome this as an opportunity to take command by opening up the discussion and encourage dissent and diversity. Learn when to set barriers and how to monitor situations for the starting conditions of emergent phenomena. In this way, women can be positioned less as reactive agents and more as catalysts within a human system. While your great idea may go unnoticed until stated by your male colleague, being able to recognize when the idea is actionable gives you the lead time needed to realize the idea, which will be far more impactful than by simply getting credit for stating it.

-

Use design-thinking.

By now, IDEO’s design-thinking approach is familiar to UX product and service designers. The approach relies on an iterative cycle of problem-finding, ideation, prototyping, and testing. Design-thinking principles have also been codified into a course topic of study intended to enable students to employ wayfinding strategies for navigating a chaotic world. Similarly, design-thinking can offer women a process for countering perceived ideas of their role and as a tool to reframe reality. Done consistently, a new reality – one that recognizes the diversity among women and men – can prevail. Is the problem really that a male co-worker believes women are less biologically suited for coding due to her stronger interest in people, or is it that he simply doesn’t understand the science? Rather than react to the problem, design-thinking provides a way to focus on the root cause and identify corrective actions.

Thanks for sharing out

Thank you for sharing these strategies, Ann! They are so nicely stated as strategies to be adopted by women and men, to help improve the UC workforce for all.

Excellent article and advice, Ann!