A collaborative group of researchers from the University of California, San Diego, traveled to Turin, Italy, recently to digitally map an entire portion of the city—complete with historic architecture, expansive murals and stunning works of art.

Digital data will be used by students and researchers on campus to explore the site’s buildings and artifacts, ultimately recreating an interactive, virtual-reality experience. Through high-resolution images and 3D models, students can study all the pieces together without the difficulty of travel to the site, nor fear of losing objects to passing time.

“The idea is to create a model— a digital surrogate—of these structures that allows us to interact with them, to analyze them, to annotate them and to make measurements to really understand their state of health,” said Dominique Rissolo, an archaeologist and assistant research scientist at the UC San Diego Qualcomm Institute. “We have a unique capability here on campus … that allows us to go one step beyond the model to actually create the digital surrogate.”

The work is being conducted as a project of the Cultural Heritage Engineering Initiative at the Qualcomm Institute, organized by researchers at the institute, Division of Arts and Humanities and Turin’s Polytechnic University.

Trip findings are an extension of Division of Arts and Humanities Dean Cristina Della Coletta’s research on the historical significance of the 1911 Turin International, the world’s fair that took place in the city’s Parco del Valentino. With a goal to visually recreate the 1911 fair, the team digitally captured a majority of the park, which includes a medieval village and the Castello del Valentino, or “Valentino Castle”—home to Polytechnic University’s architecture department.

“For the first time, we really have a wide array of expertise that is brought to bear on the project: we have engineers, working with architects, working with cultural historians,” Della Coletta said. “This is a winning combination.”

Led by Della Coletta, Rissolo, Falko Kuester and Vid Petrovic, the Turin fieldwork brings together engineering students and arts and humanities students for the betterment of both. Cross training these students, Kuester said, creates empowered and dynamic learning: just as the cultural preservation work is important, honing and testing new technical skills in the field and classroom is equally as important.

“The exciting part for us, as educators, is that we get to work with talented students from a broad range of disciplines—disciplines that historically do not really collaborate together as much,” said Kuester, the Kinsella Heritage Engineering Director at Qualcomm Institute and professor at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

“By doing this, and being able to put on these different lenses, our students get to learn to speak each other’s language [and] to communicate in ways we were never required to do before,” he said. “Our students, in the process, are becoming more complete human beings and innovators.”

Considered the initial steps in recreating the structures of the 1911 Turin World’s Fair, Rissolo said the team collected field data by using terrestrial laser scanners, structure-from-motion photogrammetry and stereo spherical giga-pixel imaging. Taking several scans from many different perspectives in the park allows the team to process the data quickly and with a high degree of certainty. They collected thousands of images, and use advanced software on campus to create digital models of the structures.

“The most important takeaway for our students is the ability to connect theory and practice, whether it is in the archives or in the digital lab,” said Della Coletta, who participated in the data gathering during fall quarter. “What makes the project meaningful is the ability of our students to learn by doing.”

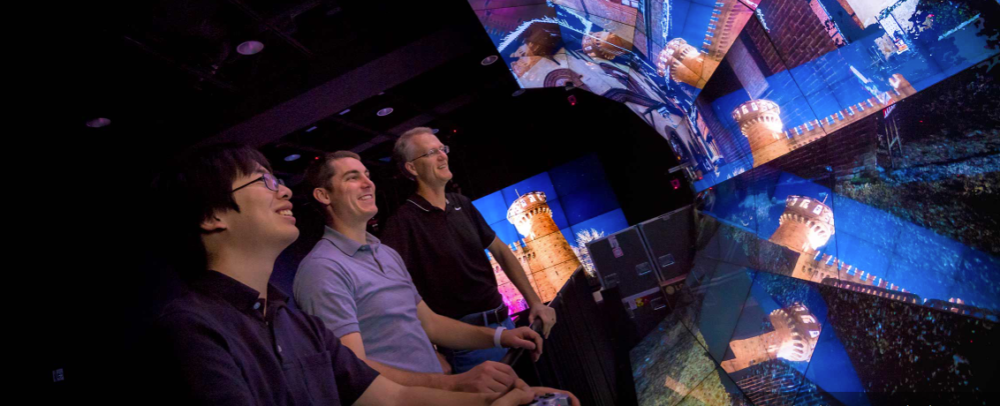

With a first round of digital information collected, the researchers have been busy on campus recreating a 3D model of the buildings, both inside and out. Viewing the models at the university’s WAVE lab, Qualcomm Institute research and development engineer Eric Lo said the results were a good representation of what he saw on the ground in Italy, but some data was missing. Once the 3D models are created, gaps appear, giving the team an overview of what to record on future trips.

“Ultimately, it’s a map to the site, but a map that also tells us what else to map in order to first create the best possible digital surrogate, combining site geometry, building materials and overall state of health, as well as its art and history,” Kuester said.

The Turin team also included Department of Visual Arts alumnus Farshid Bazmandegan and students at Italy’s Polytechnic University, headed by geomatics professor Filiberto Chiabrando. The Polytechnic team continues to digitally document historic structures in the park.

“The approach that we will follow in this project is very interesting, since it’s connected to the cultural heritage, [and] it’s connected to the humanities as well. This is a fruitful collaboration that we have started,” Chiabrando said. “The most important thing is to merge different backgrounds, and different experiences. A multidisciplinary approach is the best way.”

The Cultural Heritage Engineering Initiative at UC San Diego brings the power of student-driven engineering to the study and preservation of historic structures, archaeological sites, art and other artifacts. There are multiple projects underway, from visualizing shipwrecks near Bermuda to the Hearing Seascapes initiative with Department of Music professor Lei Liang.

“It’s a phenomenal opportunity to have the Division of Arts and Humanities partner with the Cultural Heritage Engineering Initiative, the Jacobs School of Engineering and, on top of that, the Polytechnic University in Turin,” said Della Coletta. “What better place to engage in a project that connects engineering and technology with the humanities.”

This article originally appeared in ThisWeek@UCSanDiego , February 15th 2018 and is re-posted with permission in the UC IT Blog.