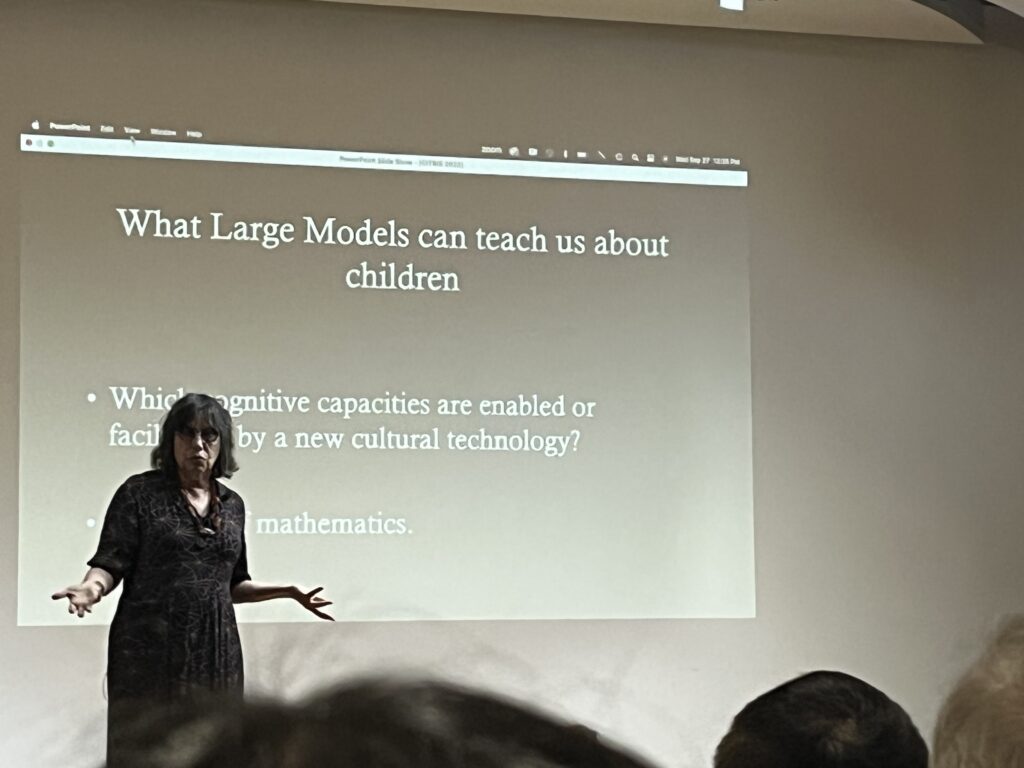

By Jackie Brown. On September 27, 2023, UC Berkeley professor Alison Gopnik presented Imitation and Innovation in AI: What Four-year-olds Can Do and AI Can’t (Yet) as part of the CITRIS Research Exchange, co-sponsored by the Berkeley College of Computing, Data Science and Society and the Berkeley AI Research (BAIR) Lab. In the presentation, she discussed findings from her recent paper, Imitation versus Innovation: What children can do that large language and language-and-vision models cannot (yet), in which she and fellow researchers Eunice Yiu and Eliza Kosoy draw parallels between children and AI in their problem-solving abilities and creative exploration. Gopnik observed that programs like large language models must maintain elements of curiosity and exploration that are inherently characteristics of young children. Watch the recording from Gopnik’s talk here.

Gopnik is a psychology professor, affiliate professor of philosophy, and a distinguished member of Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research (BAIR) Lab at UC Berkeley. She has written critically acclaimed books including “The Scientist in the Crib,” “The Philosophical Baby,” and “The Gardener and the Carpenter.” Gopnik has been recognized for her pioneering work in cognitive science, particularly in the sphere of learning and development. Her list of accolades includes being a Guggenheim Fellow, a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and Fellow of the Cognitive Science Society. She is a member of the esteemed American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and she serves as the president of the Association for Psychological Science. Gopnik currently writes for the “Mind and Matter” column in the Wall Street Journal and has shared her expertise on “The Charlie Rose Show,” “The Colbert Report,” “The Ezra Klein Show,” and “The Radio Lab.”

Reconceptualizing AI: a cultural technology perspective

Many people view AI systems, including large language models as individual agents possessing their own form of intelligence. Gopnik compares AI to the Golem, a Jewish folklore character, because both are perceived as incredibly smart and/or incredibly evil agents depending on the individual’s opinion. However, Gopnik challenges this perspective and suggests that such a binary view may not be the most accurate way to understand AI systems, particularly large models. Instead, she proposes viewing AI systems as a cultural technology which she defines as a tool that allows individuals to take advantage of collective knowledge, skills, and information accumulated through human history.

AI and the challenge of misinformation

To evaluate the social impact of AI, Gopnik cites historical examples of writing from Socrates and Ben Franklin. Gopnik compares Socrates’ opinion on writing to the current implications of AI. Socrates remarked about writing: “They seem to talk to you as though they were intelligent, but if you ask them anything about what they say from a desire to be instructed they go on telling just the same thing forever.” Socrates believed that excessive reliance on writing would diminish humans’ capacity to memorize information and make us more susceptible to accepting inaccurate content as true. Gopnik highlights the invention of the printing press as an innovation that led to the spread of information, but sometimes false information. She uses Ben Franklin’s former job as a printer’s apprentice to illustrate how humans can facilitate the spread of misinformation.

Gopnik connects these examples to today’s social implication of AI misinformation. Whenever a new cultural technology develops, norms, rules, and regulations are invented to check information. After the printing press invention, institutions and careers such as editors, fact checkers and journalism schools flourished alongside it. Gopnik observes how AI must have similar fact checking mechanisms. Gopnik shares how information from LLMs, including Chat GPT, must be viewed with caution because it is not always correct. Gopnik shares a more optimistic view than Socrates, believing that our society can use these tools to aid our day-to-day life without becoming reliant on them.

AI and children: a comparative perspective

As a psychologist, Gopnik emphasizes how children are the world’s best learners. When children engage in active learning through exploratory play, they can absorb data relevant to their problems. Children can build abstract causal models from statistical evidence, similar to experimental research conducted by scientists. Gopnik explains that while AI has a capability to accumulate information, it falls short in the domain of active exploration that young children embody. Since AI systems tend to rely on transmission learning, they can process complex data patterns but struggle to discover new truths. Gopnik’s work emphasizes that AI could benefit from the ability to incorporate aspects of innovation and exploration like a child’s learning.

Children vs AI: the “blicket detector” experiment

Gopnik’s research team used an online blicket detector to determine how AI and children process information differently. The blicket detector is a little box that lights up and plays music when certain objects are placed correctly. When conducting the experiment with 4-year-olds, most children understood the concept in 20 trials which was significantly better than any of the large language models. Chat GPT-3 and paLM regurgitated information about the blicket detector from old papers, but they were unable to play with the test and determine how the detector worked differently than previous experiments.

Gopnik shares how her role as a psychologist and grandmother helps her view the world through the eyes of children. She explains how both AI and children use reinforcement learning. However, a key difference is that AI uses reinforcement learning to solve specific outcomes, while children sometimes stumble upon findings because of active play. Gopnik notes how children are inspired to perform tests about the world around them, especially when they have caregivers to support them. This nurturing relationship grants children freedom to explore, even if they suspect outcomes could be negative.

AI progress

Gopnik concluded her talk by recapping the differences between a small child and AI. She compares today’s AI’s intelligence to a baby but hopes it can reach the intelligence of a small child. Gopnik defines intelligence as solving problems and notes that generative models do not share a child’s desire to solve problems. Statistically, an average four-year-old asks approximately 20 questions per minute due to their curiosity and desire to learn about their environment. On the contrary, AI models don’t have the capacity to “care” about their output. Gopnik uses a personal example of chess to emphasize the differences in reinforcement learning and true play. AI can succeed at chess due to its clearly defined objective. Gopnik’s granddaughter enjoys playing chess, but her own version involves putting pieces in a trashcan, mixing them up, and stacking pieces. Gopnik believes that her granddaughter is really “playing chess” and challenging the norm unlike an AI model. Counterfactual situations are significant in demonstrating a child’s ability to understand cause and effect. Gopnik suggests that if AI systems can effectively generate counterfactual scenarios, they will be able to solve problems more accurately. If able to consider a broader range of possibilities and outcomes, AI models could make more informed decisions and adapt to varied and dynamic contexts.

Community opportunity

Join UC Tech community members online to share your key takeaways and questions from Gopnik’s talk along with the previous CITRIS Research Exchange talks. Camille Crittenden, Executive Director of CITRIS and the Banatao Institute, and the UC IT Blog team are hosting this collaborative discussion on October 25, from 2-2:45 p.m. Register via this link.

Contact:

Professor

UC Berkeley

Camille Crittenden, Ph.D.

Executive director of CITRIS and the Banatao Institute

Co-founder of the CITRIS Policy Lab and the Women in Tech Initiative at UC

Author

Jackie Brown

Marketing & Communications Intern

UC Office of the President